Cesar Alves (Zare) FERRAGI

Graduate Student, ICU

【The article below is the same as the article that appears in the twelfth issue of the CGS Newsletter.】

As Japan has a biased gender approach towards the distribution of jobs (Genda, 2005), I argue that the Japanese police reproduce a similar mindset. It is centered on the figure of man as the core of the police institution, denying space for woman to actively participate in community policing activities and perform daily routine work that entail direct contact with citizens. This article will discuss gender inequalities in Japan, and how such issues might affect the Japanese police and limit the implementation of the so-called "Koban model" in other countries, such as Brazil.

Community policing implies a better relationship between the police and community, i.e. a policing approach that is friendly to citizens, respects human rights and promotes peace. However, it also requires a re-construction of gender conceptions by the police, incorporating more women within the institution and re-creating the image of policing for policeman and policewoman by emphasizing 'female' roles and qualities, such as "forging and sustaining intimate connections and practicing a more re-conciliatory, non-aggressive style of policing (Miller, 1999, p. 197)." In this light, to what extent do the Japanese police reproduce a biased gender approach within itself? Can it represent a problem in implementing community policing programs in other countries, such as Brazil?

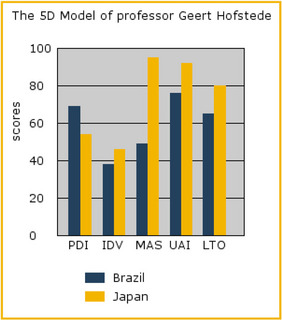

First, we can explore some cultural dimensions that differentiate Japan from Brazil. Hofstede (2001) identifies five primary dimensions to assist in differentiating cultures.1 The author affirms that Japan presents a very high masculinity index ? one of the highest among all nations surveyed (see Graph 1)? indicating that the country experiences an elevated degree of gender differentiation: males dominate a significant share of the society and power structure, with females being controlled by male authority.

Shire (2006) affirms there is a centrality of gender perception in Japan especially considering choice for jobs: full-time employment is a conception that applies mostly to men, implying a continuous process that does not allow any time for children. "The 'male breadwinner model' points to how social policies intersect with gender relations, to define men as workers and women as wives and/or mothers (Shire, 2006, p. 2)." How does Japan's 'male breadwinner model' affect the Japanese police in terms of the distribution of functions within the institution? During a few visits to Tama Police Station (in Kanagawa), I observed that while around 200 police officers were working in that station, only 10 of them were women. Men dominated most sectors of police departments, and none of the koban (police boxes) in that jurisdiction had female officers. As for the distribution of women, by department, there were: Traffic Safety ? 5; Community Safety ? 3; Criminal Investigation ? 2; Community Police Affairs (Koban) ? 0. When asked about the woman's abilities to perform traditional men's positions, including a Koban's functions, Japanese policemen  suggested that policewomen would better perform their jobs as office workers. Genda (2005) confirms that in Japan there is a hierarchy established in full-time and part-time jobs, in which women are allocated at the bottom. As for the Japanese police, work is a full-time activity in which all police officers are basically full-time employees. In this case, even if women might get involved in full-time positions within the police, they tend to perform mostly clerical work, seen as auxiliary, a piece that feeds and gives continuity to this male-dominated structure.

suggested that policewomen would better perform their jobs as office workers. Genda (2005) confirms that in Japan there is a hierarchy established in full-time and part-time jobs, in which women are allocated at the bottom. As for the Japanese police, work is a full-time activity in which all police officers are basically full-time employees. In this case, even if women might get involved in full-time positions within the police, they tend to perform mostly clerical work, seen as auxiliary, a piece that feeds and gives continuity to this male-dominated structure.

Moreover, if community policing offers the potential of forging closer connections and deeper trust between police and citizens, we cannot ignore how police organizations incorporate gender images and structures. In the first place, the Japanese Koban system differs from the American concept of community policing, as it does not seem to either present gender equity or be aware of its necessity. Therefore, how could it introduce gender equity values in the Brazilian police, considering not only the different cultural settings but also that Japan itself is gender unequal? (Hofstede, 2001; Genda, 2005; Shire, 2006). Are the Japanese police aware of the necessity of reforming the dimensions of gender within themselves, in order to propose a model to other countries?

Gender inequality in Japan affects social policies (Shire, 2006) that result in unevenly distributed job insecurities (Genda, 2005) thus attracting few female officers to community policing positions. We suggest, for example, a policy of impartial representation of policemen and policewomen inside Kobans throughout Japan, as a means to reconcile the contradictions between "masculine" and "feminine" activities within the police. Consequently, the analysis of gender perspectives within the police institution is essentially related to future prospects for the realization of not only trustful police-community relations, but also successful international cooperation on the field of community policing.

1 More details on Hofstede perspectives on culture can be found online at:

REFERENCES:

Hofstede, Geert. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2001.

Miller, Susan L.; Gender and Community Policing: walking the talk. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999.

Shire, Karen. Gender Dimensions of the Aging Workforce. Institute of Sociology

Institute of East Asian Studies, Essen: University Duisburg (draft) June 1, 2006.

Genda, Yuji. A Nagging Sense of Job Insecurity: The New Reality Facing Japanese Youth. Tokyo, Japan: International House of Japan, Inc, 2005.